By Linus Lawrence Platt

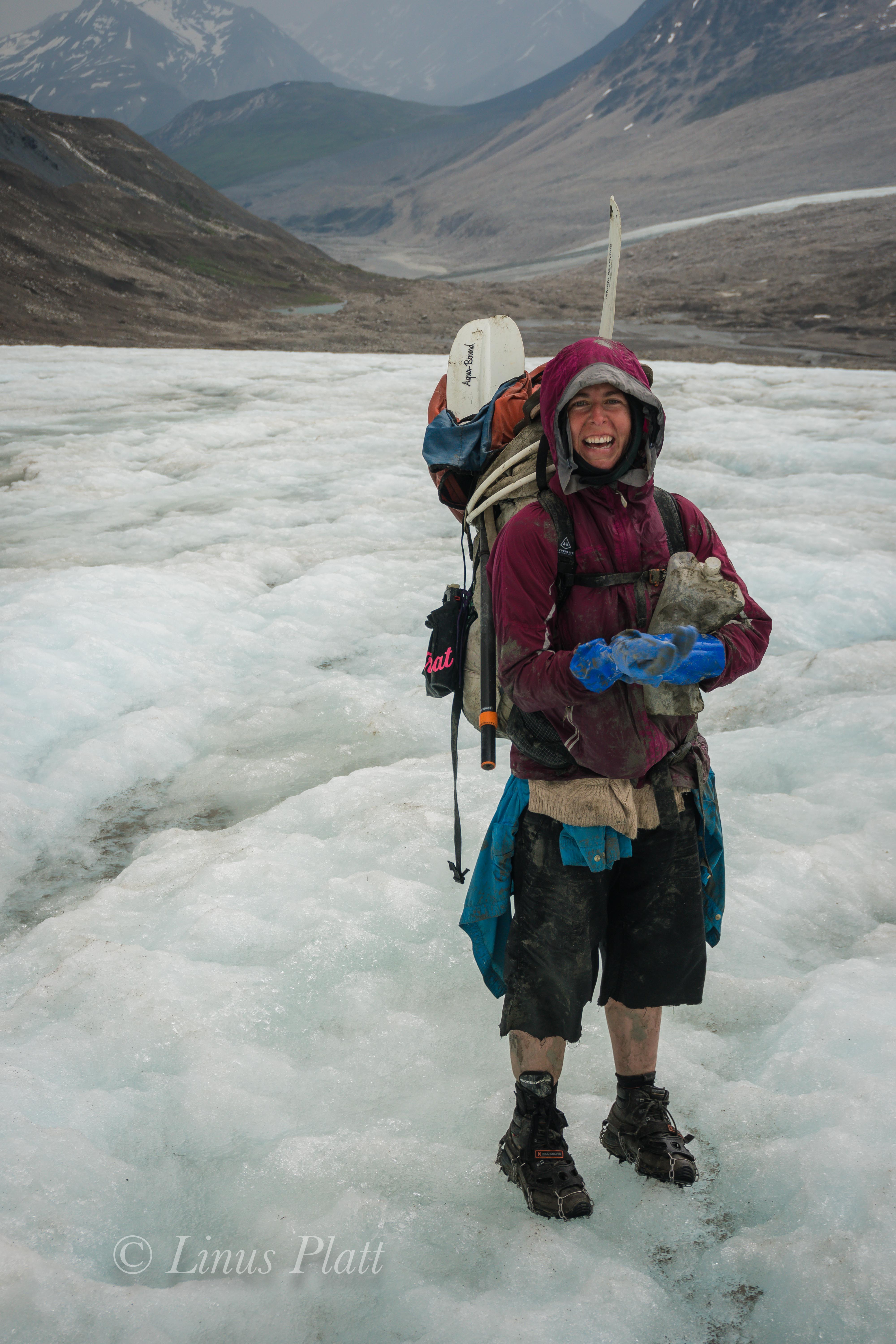

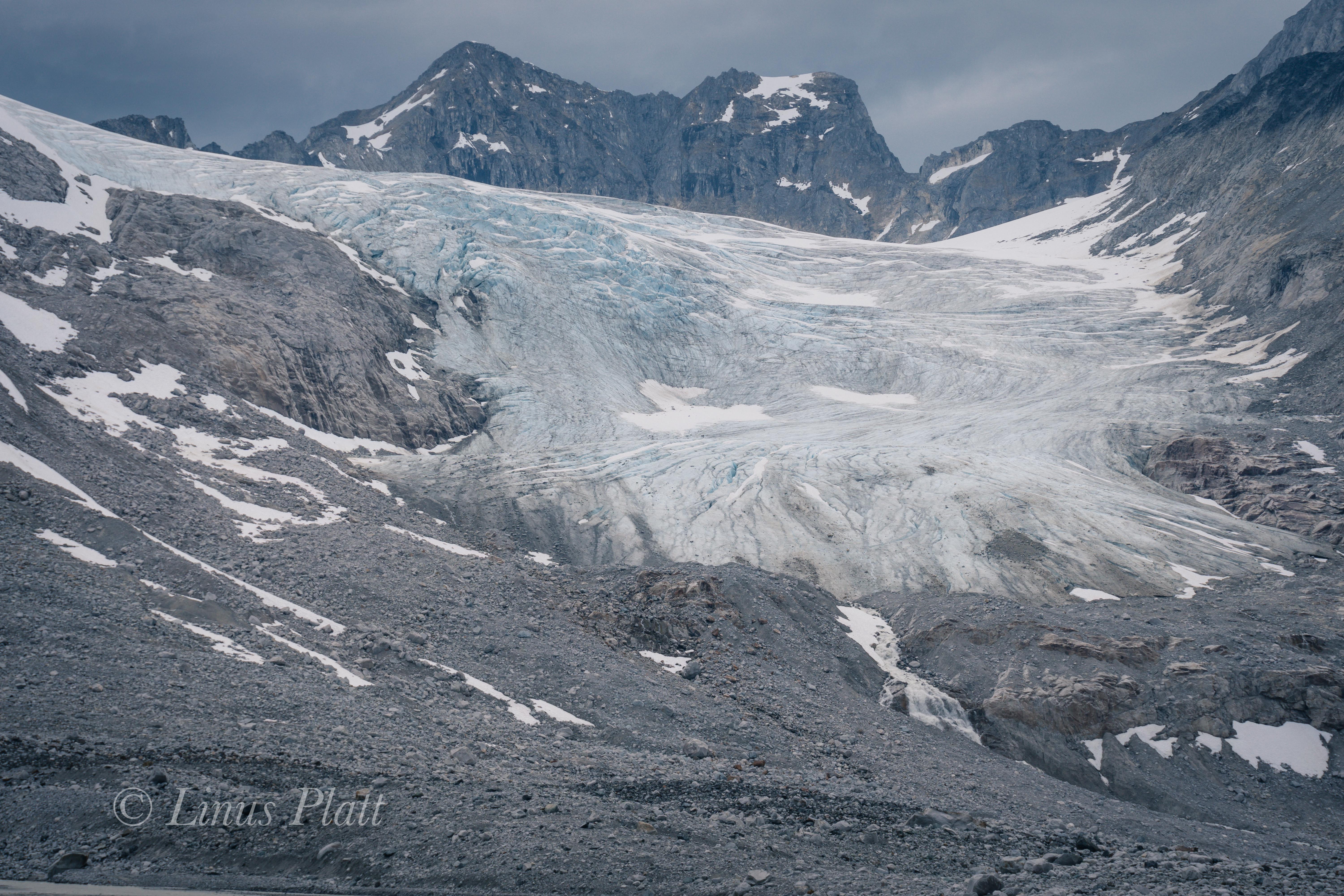

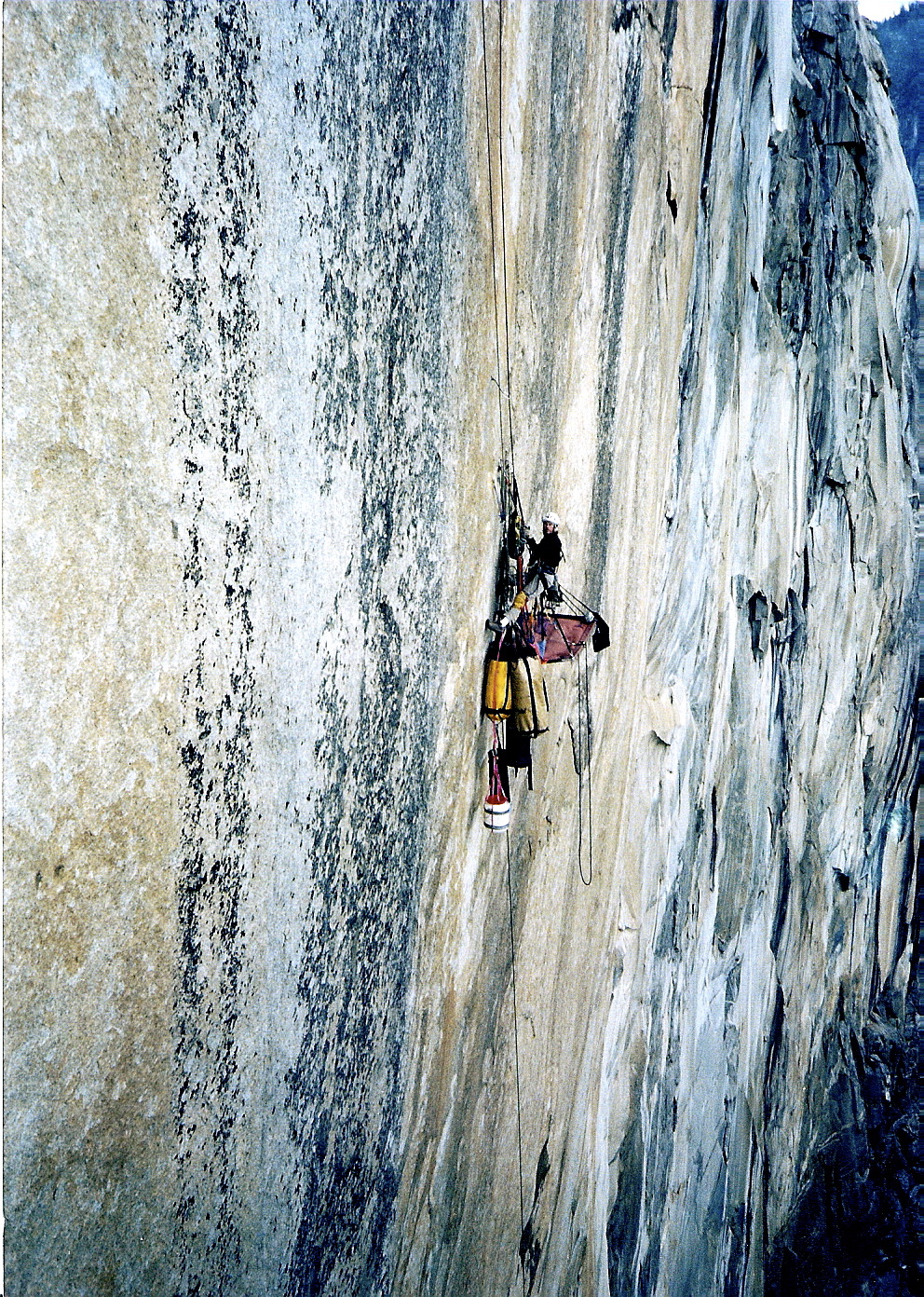

It had been over two years since the Over The Hill Expeditions gang had gotten together to hit the hills so to speak; in 2019 it was an attempt to climb and ski Mt Sanford (16,237′) the second highest peak in the Wrangell Mountains of South Central Alaska with Rich Page, Jeff Rogers, and Cameron Burns. It was trip filled with good times, friendship, and adventure regardless of our not reaching the summit. After the Sanford expedition, Rich and I conjured up a trip idea for an attempt on the East Ridge of Mt Hayes to take place the following spring, but the plandemic took shape, I lost my job, and the notion to climb Hayes pretty much went up in smoke. Disgusted with too many things about Haines, I built a custom tiny home/camper (dubbed The Raven), sold my house, and hit the road for Fairbanks to re-locate. It was later in the spring that the plan to do a packrafting trip of some sort in the summer or fall of 2021 was born.

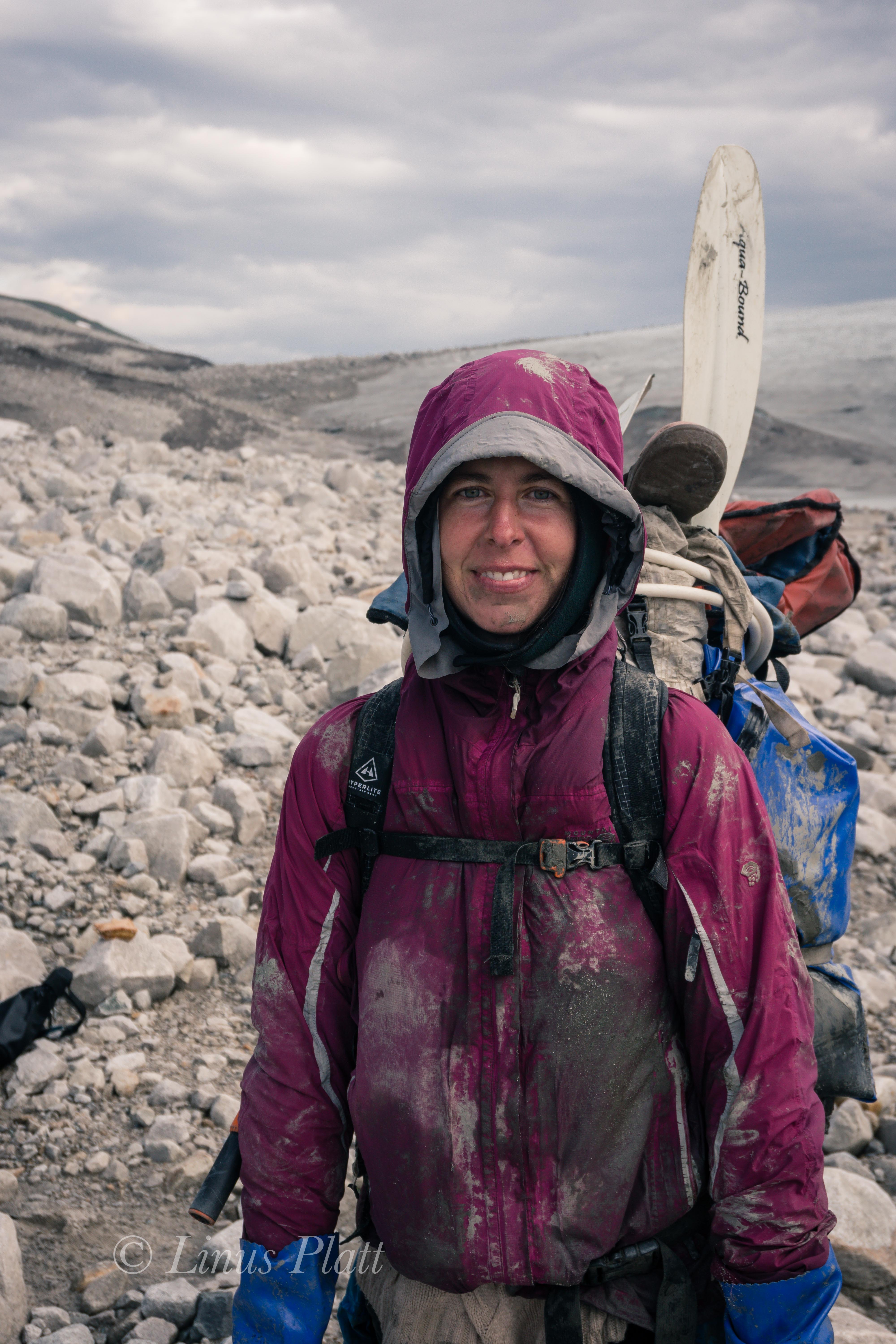

Rich, a former Denali guide from Colorado, managed to free himself from his business, Savage Gear, in North Conway, New Hampshire, of building packs and repairing outdoor gear and bought a plane ticket to Fairbanks for the end of August. Thinking a third person would be fun, I invited my friend Chris Gavin from Baltimore to join us on an adventure. Chris and I had first met in Fairbanks in 2017, and we had remained in contact ever since. We had often discussed doing some type of backcountry trip together, and when the notion of the Hayes trip was born, Chris agreed to be a team member, but of course that expedition never saw the light of day. For 2021, Rich and I mused over several possibilities, initially considering something in the Brooks Range, but the time frame for this trip dictated something further south, and we finally settle on paddling the Gulkana River from its source near Paxson Lake in the Alaska Range all the way to its terminus at the Copper River at the foot of the Wrangell Mountains in South Central Alaska. The Gulkana River is a beautiful Class II-IV river that flows through the dense boreal forests of Central Eastern Alaska, ancestral home to the Athabascans, and a major tributary to the world famous Copper River.

After losing my job in March 2020, I spent an entire year building The Raven, remodeling the house for re-sale, and modifying and repairing both vehicles for my departure in April 2021. It was an exhausting period with little time for much else. For me, leaving Haines and relocating to the interior was no simple task; I had two trucks, a home built truck cabin, and a cargo trailer that held my carpentry tools and the bulk of my belongings. It took the last year in Haines selling, giving away, and throwing out material possessions to make this happen. In a time when most Americans are busy collecting things and spreading out, I am quite content, ecstatic in fact, to be reducing my world load and becoming as compact and efficient as possible. Even still, not one, but two trips had to be made to Fairbanks. The first would be in the Toyota truck pulling the cargo trailer and stashing both at my good friend Tony’s place in Fairbanks, then flying back to Juneau, taking the ferry back up to Haines, and repeating the process; the second time armed with the Ford F250 and The Raven, my custom made truck cabin built with Alaskan winters in mind. Of course, with Canada closing its borders to “non-essential” travel (all travel is essential, for one reason or another) this made for a tricky escape out of Southeast Alaska. Luckily, my buddy Sven wrote me up a semi-fake employment agreement, and by the skin of my teeth, I made it across the Canadian border 40 miles from Haines. When I finally got back across the Alaskan border and arrived in Tok, I literally got out of the truck and kissed the ground. Back in the Real Alaska… After arriving in Fairbanks, I got a post office box, changed my driver’s license, car insurance address, and vehicle registration. And just like that, I was now a resident of Fairbanks, ensuring the Canadian Border Robots would give me a pass on the 2nd trip. My primary concern after the fact is that they would remember me from the week prior (I have a very unique and somewhat memorable name) Alas, it was a non-issue and and before I knew it, The Raven and I were camped along the Gerstle River near the Alaska Range in one of my favorite parts of the state. All said and done the escape from Haines was literally the single most difficult task yet in my lifetime. Not long after, Angela boards a ferry with her truck bound for Whittier, and makes the drive to Fairbanks. She too had felt the need for something different than what Haines has to offer.

Haines, Alaska… well sort of Alaska; it feels a bit more like a Canadian province than a de facto Alaskan town, is a beautiful place indeed, but contrary to the arrogance of its locals, Haines does not in fact have the monopoly on “Alaskan Beauty”. In fact the Central Interior with its majestic mountains, enormous glaciers, rivers, forests, and expansive valleys are far more appealing to this soul. As are the people and the weather; I found Haines, and by a margin, the people (especially the outdoor adventure community) of Haines to be somewhat cavalier and impudent. Obviously this does not apply to everyone; there are a number of Haines-folk whom I hold in high regard and have the deepest respect for (you know who you are). The winters are heinous for the most part, where it will snow, then rain on top of snow, then freeze, then turn to ice, then repeat… all winter. I’ll take minus 20 degrees F in the semi-dry subarctic climate of the central interior over the plus 30 degrees F and 90 percent humidity of Haines any day of the week. After nearly 8 years living in Haines, I’d had enough. So back to from which I came was in order (I’d lived in Fairbanks for a stint prior to taking up in Haines).

The entire spring and summer was filled with many, many work and carpentry projects for my good friend Sven at his Hostel, converting an old cabin into a genuine public espresso shop, getting my own scene together on my friend Tony’s land at a place I now dub The Raven’s Roost, cutting firewood for the impending winter, and countless other activities regarding work and life preparation. In between all of this, I still managed a day trip to the Alaska Range, a three day fly-in trip to the Brooks Range, a two day pack rafting trip on the upper Chatanika River with Sven, another 2 day driving trip to the Brooks, and several other hikes and forays into the fantastically beautiful White Mountains just outside of Fairbanks. The Raven’s Roost is a good place to throw down for an undetermined amount of time; it sits on several acres of boreal forest, is mostly quiet and private, is close to town (3-5 miles), and on appropriate days, just down the hill from my place, one can see all the high peaks of the Central Alaska Range dominating the skyline.

By the time late August rolled around, I was deeply ready for a needed break; I had only paddled once all summer, and it was a good one. Sven and I paddled a great two-day trip down the upper Chatanika, a beautiful class II paddle on the edge of the White Mountains where we paddled for almost 11 hours straight the first day, finally landing on a good camping beach where we roasted sausages on an open fire, sipped whiskey, and had some laughs.

On August 26th Chris Gavin flies in and having a few hours to kill, we step out for Thai food at the consistently great Lemongrass Restaurant, followed by a tour of my Raven tiny home. Once Rich arrives a few hours later, it’s game on to get organized and gear together at Sven’s hostel. The next couple days are spent roaming town in search of this and that, generally followed by a steak or Sockeye Salmon BBQ from when Sven and I had dip-netted in Chitina weeks before.

August had been a typical rain-fest, and honestly the weather was downright miserable (this IS Alaska after all) in the days before we headed out for the drive down the Richardson Highway toward Paxson Lake, but as luck would have it, the clouds part the morning we start driving and one might even consider it a beautiful day. With Chris and Rich driving my Toyota pickup, and me in the lead driving my big Ford diesel, we caravan south through arguably my favorite part of the state. It is here that the Richardson passes through the Central/Eastern Alaska Range and has been the scene of many mountaineering and hiking adventures over the years. Our destination and put in is Paxson Lake, just south of Isabel Pass on the Richardson Highway about three hours south of Fairbanks.

Paxson Lake is fairly large glacially fed lake in Alaska’s interior that is about 12 miles long by about 4 miles wide, and is home to Lake Trout, Dolly Varden, Northern Pike, Burbot, two species of Whitefish, Arctic Grayling, and hoards of spawning Sockeye Salmon from June through September. There is also a King Salmon run in June. The BLM operates a campground and a boat ramp on the east side of the lake, so we opted to spend the night here and get ready for the several mile flat lake paddling tomorrow. The Gulkana River begins its life born from Summit Lake a few miles to the north, where it runs very thin down a treacherous class IV canyon before entering Paxson Lake, where it drains at the Lake’s southern end.

Late that night, from a deep slumber within my tent, I hear Chris outside trying to wake us as the Aurora Borealis is out and wildly going off. I dress quickly and scamper out; the sky is ablaze with one of the true gifts from the north. Chris and I decide to take a walk to the lake shore to catch the show, and seeing the brilliance dancing above the peaks of the Central and Eastern Alaska Range reminded me of why I live in such a beautiful, challenging, and sometimes inhospitable place. Alaska is a genuine treasure 12 months out of the year, and calling its interior my home is something I am extremely happy about and proud of. After the show fizzles down, we walk back to camp and hit the rack.

The morning of September 1st, Chris and I do our truck shuttle to Sourdough Camp further south down the Richardson Highway; luckily we have two trucks so this is an easy operation, save for one minor detail. When Sven and I had gone to Chitina to dip net for Sockeye weeks earlier, there was and still is a major road re-construction of the Richardson, with multiple delays along a 20 mile stretch. I had completely forgotten about this fact when Chris and I rallied south, but ultimately it only added about an hour to the task.

Back at Paxson, Rich has everything laid out and we pack the boats, inflate, and hit the water.

It feels good to paddle and luck is on our side with no headwind. After a couple of hours on the lake, we reach the beginning of the Gulkana where hundreds of Sockeye are spotted in the depths beneath our rafts. This clearly a spawning bed, with as many dead fish as alive. We pull off to a bear trampled area and have a welcomed lunch.

The next section is the real beginning of the Gulkana proper with long, fast and fun sections of class II waves and rollers. After a spell, an old trappers cabin from the late 19th century gold rush era appears and adorning a nice flat and grassy camp spot. We pull off and settle in for the night. The weather is now certifiably glorious and watching the sun set behind the Taiga sees me happily drifting to sleep. Later in the evening, a Cow Moose and Calf zip right past my tent and fjord the river. More Alaska wonderment that makes everything seem all the more special.

The morning brings ethereal mist and mesmerizing light over the enchanted Alaska landscape, and later in the morning we see more Moose both in the river and in the woods on shore. The critters are out and about. This next section is fairly slow and twisty as the river makes its way through the thick taiga of the upper Copper River Basin; an immense area that once held the enormous prehistoric Lake Atna that formed during the Wisconsin Glaciation period more than 40,000 years ago. The lake was formed when what is now the Childs Glacier grew and subsequently dammed what is now the Copper River. After the glaciation period ended, the glacier receded, draining the lake. The Lake Atna basin is fairly flat and covered in Boreal forest with several remnant lakes remaining, one of the largest of these being Lake Louise, a popular fishing and camping destination for Alaskans during both summer and winter. Later, a few splashy sections follow here and there just to make sure one is paying attention, which we must do in order to spot the take out for the upcoming Gulkana Canyon portage. I had been eager to get to this place in order to scout the Gulkana’s biggest rapids in hopes of running them, but after close inspection, I decide that it is better to portage and live to paddle another day. These class III/IV boilers and pour offs looked dangerous to me, and being at least 40 trail-less miles from the highway means be fucking careful.

This section of the river at the canyon was a special place for sure; the roar of the rapids, the granite walls and boulders, the Bear trails, fishing holes, and great camping spots impose upon us the idea of doing no paddling at all the following day and instead do some hiking, fishing, and relaxing.

A nice late sleep in the morning followed by a lengthy round of coffee finds us wandering Bear trails up river to have a good hard look at the Class III/IV chaos in the main canyon. The roar is deafening in spots and there are good side trails leading to the waters edge for close inspection of the drops and hydraulics. I had it in my mind that I might reconsider running the canyon rapids today. One very noticeably absent feature of this canyon is any trace of a real eddy line. On the contrary, there is a significant undercut that looks difficult to avoid. I stick to my decision not to run it, and Chris, who also had notions of running it today, decided to duck out as well in the interest of group safety being this far out from rescue or medical attention. Rich did bring along his Garmin InReach GPS communicator for emergencies, but regardless, pushing the envelope seemed a bit reckless to me. It might have been different if I had been paddling a ton all summer, but sadly this was simply not the case. Upon returning to camp, Rich surprises us by whipping up a batch of Cinnamon rolls on the MSR stove, complete with sweet frosting and hot coffee. We sit with our treats and listen to the roar of the river and I watch as a pair of mated Ravens chase one another through the treetops, each one changing the conversation between them frequently with yet another sequence from their extended vocabulary. The Ravens always have a special place in this world to my thinking and Ravens on the Gulkana that much more so.

A bit later, Chris and I decide to hike up to Canyon Lake, for which there is actually a trail, which in most parts of the Alaska backcountry is pretty much unheard of. The “trail” as it turns out is a muddy, rutted Moose path complete with anticipated bushwhacking. We reach the tiny little lake and being somewhat underwhelmed by it’s size and presence, we turn back and head back to camp. Later, we glance at the map, and Canyon Lake is a much, much bigger body of water no more than 5 minutes further past the pond we visited. Ah well…

Next, we decide to partake in an effort to catch some fish for an anticipated fish taco feast later in the evening. Chris and I grab rod and reel and head downstream to a hole we had spotted earlier on our hike. The very first cast I nab a 17″ Rainbow Trout, and over the course of about 10 minutes, had another smaller Rainbow, and two nice Graylings. All caught using spinning gear with a small sized spoon. Four fish is plenty to feed the three of us for supper I reckon. After cleaning the fish, I build up an existing campfire ring with more river rocks to create a nice oven-like enclosure. Next, a trip up the hillside to a stash of firewood I had spotted earlier, and we were ready. I crank up the fire, wrap the fish in aluminum foil, sprinkle with olive oil and salt, and crack open the bottle of whiskey for a round of shots between us as we feed the fire and wait for the ensuing coals to develop. Soon we are munching delicious fish tacos and feeling quite content. Later, Rich, in his usual Denali mountain guide style, puts together a grand cheesecake adorned with fresh blueberries picked on site, and serves it up adorning his fake hillbilly halloween teeth set. A good laugh was had by all and as darkness set upon us, we hit the sack. At 2 am I hear Chris outside rummaging around and rapping about the explosion in the sky. I’m out of the tent in a flash and setting up camera and gawking at the miracle above. The Aurora was out and taunting us again, this time spread across the sky in a dazzling display of brilliance and color from horizon to horizon.

In the early morning hours, I wake to the pitter patter of a steady rain on the tent, shrug it off, and roll back asleep. At 9 am, still in the tent, the rain seems to be letting up, but the silence in camp is tell tale; no one in camp is eager to get up and pack things up wet. As many hundreds of nights I’ve spent in the wilderness and packing it in wet, the task eventually becomes routine, yet is never enjoyable no matter the level of efficiency. After a damp round of coffee and breakfast, we pack it in and hit the water. The rain has all but stopped, but there is a chill in the air that has mostly been absent so far on this journey. For the first time, I’m wearing gloves and beanie, and under my drysuit are layered clothing. The river is outstanding today… loads and loads of twisty rapids, beautiful scenery, and the ever present sensation of being deep into an Alaska back country adventure.

In looking for a camp spot on rivers, I like the sort of gravel beach that meets certain criteria; the size of the gravel need be small, not too many fist sized rocks, but a good mix of gravel, a little sand, and possibly a few larger rocks for a wind break if a fire is desired, and I always look for stashes of driftwood to make said fire. Additionally, I look for ones that are elevated a bit from river level… not much, perhaps only a foot or two to keep a potentially fluctuating water level at bay. Of course it must also afford flat areas for pitching tents and such. Luckily, the Gulkana is graced with many of these aforementioned bivouacs. On this day, it seemed we had been paddling for a very long time; it wasn’t any longer than the other days, but we were all feeling a bit exhausted and felt accordingly, so when an ideal camp appears meeting the above requirements, we pull off, set up tents, and build a nice fire, mostly just for the psychological comfort a camp fire can provide. The nearby river line is dotted with extremely large King Salmon skeletons and skulls, remnants from the run many weeks earlier. A Grizzly Bear track or two lets us know we share this beach with others. The sun sets and a brilliant display of color paints the sky over a vast section of taiga adjacent to our camp as I crawl into my nylon cocoon and sleep like the dead.

The next day, we anticipate making it to Sourdough where the truck is, and within a few hours, it comes around, and after deflating packrafts and peeling off drysuits, we pack the truck loosely, pile in, and head to Glennallen about 35 miles down the Richardson. After picking up dinner supplies, diesel fuel, and beer, we drive back north to Sourdough and setup a fine truck camp and have a feast of New York Strip, baked potatoes, and a much welcomed salad. Anything but the usual backcountry food and freeze dried meals we normally carry was a treat to the tastebuds and body.

After breakfast and coffee, we decide to keep paddling to at least the Gulkana River bridge near the native village of Gulkana, where the Richardson Highway passes over the river. Many of the accounts we had read spoke only of the section of river north of Sourdough, as the BLM designates that section as “wild and scenic”, which is really nonsense, since the entire river certainly meets that description. To our absolute delight, the section of river south of the “scenic and wild” designation, and the section that few people paddle, turns out to be possibly the best section of the entire 85 miles of river. The river at this point is twisty, fast flowing, and full of many, many class II/III splashy sections. Furthermore, the beauty of this portion is really outstanding, with countless 300 foot high cut banks displaying the colorful geology of the area. Additionally, the fall colors are mesmerizing. Mother nature has painted the landscape all measures of gold and orange hues. The river is big here as well, with hidden boulders and pour offs difficult to see from upriver, commanding one pay close attention. Another long day ends at a good beach camp with a striking view of Mt Drum (12,010′) gracing the horizon.

The following day, we arrive at the Gulkana Bridge, where we ponder the options of either stopping here and hitching to the truck, or continue on to the Copper River and paddle down it a day or so to the community of Copperville. For whatever reason, there was some tension developing between us, and after some poorly concocted discussion, we decide to keep going, which pleased me as I really want to paddle the Gulkana in its entirety. After a couple hours, I see the big, open drainage containing the mighty Copper River, and soon the Gulkana’s crystal clear water slices into the glacial silt of the Copper, creating an often seen phenomena in Alaska when two rivers of different origins merge. Both the Copper and the Gulkana are born of the ice, so it might make one wonder why the Gulkana is clear and the Copper is silty, and as far as my thinking takes me, it is because the Gulkana passes through Paxson Lake near it’s headwaters where the glacial silt is filtered, where as the Copper is a wild and raging specimen shooting directly from glacier to sea.

The Copper River is a beast of a river, born straight from the monolithic mass of Mt Sanford, and known for its treachery, volume, and history, both modern and ancient. It is also known for being festooned with one of the worlds largest Sockeye Salmon runs, As soon as I hit the main Copper channel, everything feels like it went up a notch or three. I suddenly feel intimidated as the sheer size and volume of this mighty river is a whole different experience compared to the little Gulkana. Several days earlier, at a Bear print covered beach where we ate lunch, I managed to paddle off, leaving my PFD behind, and it wasn’t noticed for at least an hour downstream. Now here, on the Copper River, without a PFD, and Rich’s rental packraft, an old school Alpacka boat with a leaky spray deck taking on water, we pull off onto an island in the middle of the river to contemplate the situation.

The main channel we must take looks a tad uncivilized for both Rich and I with our said equipment disabilities. Chris was the only one in the group currently equipment-rich, but we all decide to ponder the possibility of escape. The issue is the main channel that separates us from the highway side of the river. The water is fast and cold. I am suddenly thrown into a psychological battle with myself as a similar scenario last summer on the Klehini River with Angela arises in my thoughts. We decide that the best way is to start a Hairy Ferry (paddling upstream in order to make a crossing) at the most upstream point on the island. Chris goes first, with Rich and I downstream with throw lines in hand ready for a rescue if needed. I see Chris paddle as hard as he can, fighting the current in an attempt to keep the boat pointed upstream. If the not done correctly, the bow will catch the current and turn downstream. If that happens, our plan will fail, and a commitment to the raging channel will ensue, putting us in a much more dire situation. Chris makes the next island, where he pulls boat up on gravel and pulls out throw bag for the next participant, which is me. I paddle like my life depends on it (it does) as adrenaline carries me to the second island. Once again, Chris and I are in rescue mode as Rich makes the third crossing. Since we are on yet another island, we must duplicate these maneuvers one more time, this time matters most as wave train in the main channel could grab us if we are not extremely careful. After another adrenaline fueled crossing, we are on the western bank of the Copper River, and an unknown number of miles from the highway. Had we continued down river to Copperville, we would have been all set to simply hitch hike to the truck at Sourdough, but here, we are at the confluence of the Gulkana and Copper Rivers essentially in the wilderness, unwilling to paddle further, with an unknown and trail-less escape to the highway, which we have no idea it’s distance.

We shortline the boats up a sizable embankment utilizing our rescue ropes and find a pretty nice flat section overlooking the river in which to make a camp. We are all in good spirits since the escape incident went without harm or injury, and we polish off the last of the whiskey, eat a quiet supper and get some sleep. In the wee hours of the morning, it rains solidly, and thus, coercing the three of us to sleep late as per normal during the wet spells. After packing up everything into packs, we shoulder the monster loads, and follow a faint Bear trail north, where we turn west when a drainage appears. Soon we are soaked to the bone from bushwhacking in the wet taiga, but soon it appears we are on track and heading due west toward the Richardson Highway. After an hour or so, I hear trucks on the highway, and without further adieu, we stand on the shoulder of the pavement, feeling pretty ragged and worn. I toss down my bloated pack and begin to stomp north with my thumb out as Rich and Chris guard our packs.

After two separate rides, the first being a couple of Native folks from Gakona, and the second, a Native man from Slana, I’m at Sourdough and walk the quarter mile to the truck. Soon I’m back with Rich and Chris, where we decide to drive to Glennallen for supplies and afterward make the drive back north to Paxson Lake where the other truck is. The next morning a nice

late start sees us happily entering the Denali Highway, 135 miles of glorious dirt road traversing the Central Alaska Range. It had been a few years since I had been out here and was shocked at the sheer number of hunters. Dozens upon dozens of hunting towns of RV’s and 4-wheelers are scattered about the landscape, making it clear there are literally thousands of people out here for the Caribou hunt.

Over a decade ago I rode my bicycle to Alaska starting in my home of 21 years in Moab, and after 3800 miles of pedaling, I found myself on the Denali Highway on a hilltop camp over looking the giants of Mt Hayes and Mt Deborah, the Clearwater Mountains, and the headwaters of the mighty Susitna River. It was at this exact hilltop camp, found by pushing my bicycle up old ATV and game trails, that I fell in love with Alaska and it was at that very moment I vowed to make it my home forever. It was mesmerizing to see this exact place again years later and even more so with the fall colors of the Willow, Blueberry, and Tundra on fire… I named this place Revelation Hill and without a doubt in every way it changed my life forever.

That nigh, camped at Brushkana Creek near the western end of the road, we witnessed yet another spectacular showing of the Northern Lights. Time after time, it never fails to remind me of what a gift the far north is to me. Late that afternoon, we roll back into Fairbanks, where I drop off Chris and Rich at Sven’s and I head home to The Raven to sleep in my own bed for the first time in 12 days. In all, we paddled over 85 miles and spent 8 days on the river including the rest day at the Gulkana Canyon.

A couple days later, the three of us embark the final paddling adventure of the season and hit the Upper Chatanika and repeat the trip Sven and I had had done back in June. Once again, the fall colors are off the hook, and the water levels are surprisingly high, making for an outstanding paddle. That said, the night time temps are dropping and I can feel Old Man Winter poking his head in the door. A couple days later, Rich and Chris board airplanes bound for home and I head home to Raven’s Roost, a hot cup of tea, and a ponder of the coming winter.

You must be logged in to post a comment.