One of the biggest factors in Leaving Haines after 8 consecutive winters living there and moving back to Alaska’s vast interior was simply a matter having access to both the Alaska Range and the Brooks Range. Fairbanks is a great focal point for both, especially for the central and eastern parts of the Alaska Range, and equally so to the monumental Brooks Range, one biggest and most remote mountain regions on the planet; a place to fill a dozen lifetimes worth of exploring.

For me, summer 2023 was getting off to a late start. At least that’s how it felt. What was originally proposed as a start to our work projects at Takahula Lake in mid-late June, began in earnest here in Fairbanks the first week of July. I spent that time cutting trees and clearing a site for a future cabin build here on my property in the Goldstream Valley to the north of Fairbanks. Eventually, my workmate Richard Baranow arrives in town, and along with our other workmate Jared Brantner, we embark on several days of material purchasing and logistics for three people, two dogs, and over 12,000 pounds of food, tools, building materials, and supplies for 8 weeks worth of construction projects. Our project site is a cabin situated on the shores of Takahula Lake, located within the Gates of the Arctic National Park and adjacent to both the Alatna River and the Arrigetch Peaks region.

Bettles, Alaska, located over 200 miles north of Fairbanks, is a tiny village situated along the prominent and historic Koyukuk River and home to less than thirty people. Angela has been living there recently for her new job at the Bettles weather watch station, but with all the chores at hand unloading airplanes and organizing, we barely have time to see one another. The launching point for a most trips into this part of the Brooks Range generally begin here, with an airstrip that can receive both small and large aircraft; and from which smaller bush planes can take one deeper into the heart of the Brooks. From Fairbanks, we charter a Cessna Caravan via Wright Air Service to get the three of us, the two dogs Taka and Hula, all of our personal tools and gear, and a weeks worth of food to Bettles. For the remainder of our nearly 10,000 pounds of lumber, food, and building materials, a Curtiss C-46 Commando is employed and scheduled to arrive in Bettles that very same day. Once in Bettles, the task of unloading and organizing everything was at hand so it could all be flown the 60 plus miles to Takahula Lake with smaller 1000 pound loads via DeHavilland Beaver, an aircraft of legendary status in the world of remote Alaska bush flying. After a couple days of rain in Bettles, I say a quick goodbye to Angela, and we climb into the Beaver with dogs, food, and tools bound for Takahula Lake

Heading west and flying just south of the massive Brooks Range divide, we follow the Koyukuk River before crossing both the Wild and John Rivers, then sneaking past the Alatna Hills and up The Malamute Fork that eventually leads to the Iniakuk River and the Alatna River, one of the central Brooks Range’s primary water systems. We turn north, just past Iniakuk Lake, where we drop into and continue up the Alatna river until Takahula comes into view. Flying over the Brooks Range region in the summer is a special treat, with literally hundreds of rivers, creeks, and ponds visible among the endless valleys and countless summits both un- named and many un-climbed. It’s vastness is quite overwhelming and getting ones mind around it’s true size is somewhat mind boggling. Soon, the 1957 DeHavilland Beaver touches its floats down on the lake surface and we find ourselves taxiing towards the obvious cabin on the northeast corner of the Lake. The next several days are spent organizing load after load from Bettles, getting our camp up and running, and handling some preliminary work details to align the summer’s work projects.

Across the lake, a prominent, sharp limestone peak commands our attention every single day after work as we eat our supper on the cabin porch overlooking the lake. Richard names it the Hula Horn after his lovely pooch Hula, whose namesake is also born of the region. After a couple of weeks of hard labor and accomplishing a portion of our set goals, we decide that a break is in order, and we set our eyes on the Hula Horn, which according to Richard, is most likely unclimbed.

The following day at around noon, we load up the canoes and paddle to the southwest side of the lake, where there is a large beach and is a popular spot for folks coming down the Alatna River to be picked up. It is one of the very few camp spots on the lake, and is thus overused and worn. We stash our canoes here and begin hiking north along the shore of the lake, searching for a way around the obvious tussock swamp adjacent to it. Once found, we make our way through the low lying taiga and aim for a high rocky point on the ridge, where once gained, a short thrash down a gully system leads us to the edge of the beautiful Takahula River. Regretting not bring a pair of running shoes or sandals for river crossings, I roll up pant legs and cross the knee deep torrent of ice cold mountain water barefoot. Richard has brought a lightweight pair of hip waders and crosses with the two dogs in tow with ease. Jared manages the crossing in his socks, and soon we are hiking up the sparse boreal forest towards another high point where just below, another river crossing awaits. This river, an un-named creek at the foot of the Hula Horn itself, we name Freya Creek, after Taka and Hula’s mother. Freya Creek is much narrower than the Takahula River, but it is deep, fast, and icy. In fact, it is narrow enough to allow Richard to go first with his deluxe hip waders, then once across, he rolls them up and tosses them to each Jared and I to use. Soon we are aiming for lightly vegetated areas comprised of mostly lichen and moss; interestingly, these areas tend to be dry and very easy to travel upon. Eventually, the going gets steep and we are skirting a great limestone cliff of perhaps 150 feet in height; at it’s top, the terrain is steeper yet, where it becomes what one might call class III or IV moss. At the top of the steepest section, we now find ourselves at tree line just below the North Ridge leading up the Hula Horn. A short scramble past a lone Spruce tree puts us on the firm tundra and lichen covered ridge, where we rest for a spell and take in the outstanding views of Takahula Lake, Takahula Peak, the Alatna River, and the several dozen un-named peaks surrounding the area.

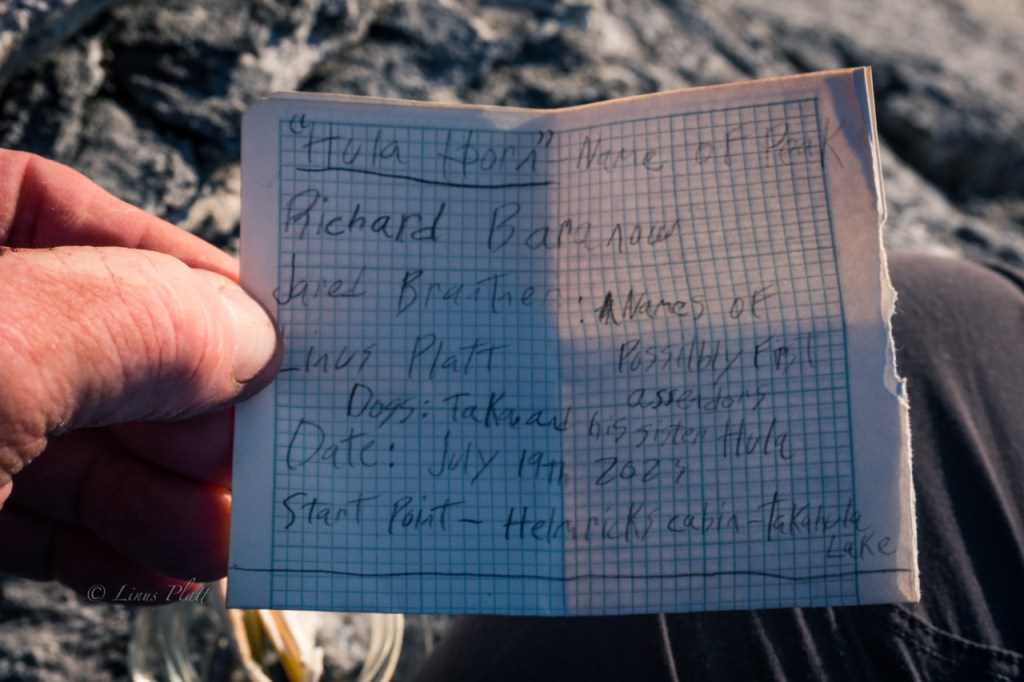

From the ridge, the walking is incredibly casual where one meanders open tundra, Caribou trails, and skirting small limestone outcroppings to one side or the other. After a good long section of these pleasantries, the route becomes, steep, loose, and muddy. Jared being many years younger than both Richard and I is far, far ahead of us, and I catch a glimpse of him and the dogs on a shelf about a half mile off and many hundreds of feet higher. Richard and I are running low on water, but a seeping spring oozing from a mud entrenched limestone shelf provides relief to our searing throats and near empty water bottles. Ahead, the route continues its steepness; yet treacherous sections force us to begin skirting and scrambling to the west side of the ridge, where after a multitude of nuanced zig zags deposits us below a cliff band below the summit block. Jared is seen up near the summit, and the dogs are left below, where Richard ties them up out of harms way. Up a short limestone crack system with a couple of moves of class IV rock climbing and we are standing on the narrow rocky summit. The view from the top is mesmerizing; the long and jagged line of granite of the fabled Arrigetch Peaks stretches out before us, and way, way off to the west, the thin outline of Mt Igikpak (8510′), one of the highest peaks in the Brooks can be just barely seen. Igikpak lies in a remote region near the headwaters of the wild Noatak River, and was first climbed in 1968 by David Roberts, Chuck Loucks, and Al De Maria. Since then it has only seen a handful of ascents. To the south, endless valleys, rivers, and un-named peaks stretch for as far as the eye can see, leading to more unseen rivers and drainages feeding the Yukon River region of central Alaska. To the north and east massive peaks dot the horizon before the landscape gives way to the arctic plain commonly referred to as the North Slope. We build a cairn, sign our newly made summit register, and begin the long descent down the zig zagging traverses and rocky scrambles that lead to easier walking along the tundra covered ridge. Once back in the forest, the mosquitos come out in hordes and we make haste back to the canoes, where a paddle across the lake at almost 2 am in the Alaska twilight has me nearly passing out from exhaustion. 14 hours after starting the Hula Horn, we are back at the cabin sipping beer and eyeballing the peak we had just climbed.

The next day is spent doing absolutely nothing, but over the following days and weeks, we put a good dent in our primary work goal for the summer: a 16′ X 25′ wooden framed deck with a steel framed vinyl storage tent erected on its top, which is to serve as storage for the entire cabin site and 5 acre property, holding everything from tools and building materials, to hiking and backcountry gear, to hunting and fishing equipment, to fuel, propane, paints, goods, and supplies of most anything imaginable that one may need at a remote Brooks Range outpost.

A couple of days before we are scheduled to be picked up and flown out, I decide to head up the Takahula River solo to inspect and potentially packraft it. So late one morning I pack up my backcountry kit, inflate my raft, and paddle across the lake where I’m able to easily hike over the ridge to the Takahula drainage below. At river’s edge, a crossing is unrealistic and an epic bushwhack ensues up river, where I’m forced up a hillside to avoid the worst of it. Eventually the thrashing subsides slightly as I’m gaining altitude and the forest is thinning. A great set of rocky and turbulent rapids steers me up to a rocky vantage and some spectacular views of the previously unseen mountains to the northwest near the Takahula headwaters come into sight. Looking back downstream, I now see the Hula Horn; this time from an impressive alternate perspective. It’s elegant and complex lateral ledges and zig zags ever so visible. I descend the rocky point into an open stone filled valley situated at the foot of Takahula Peak near it’s west- north-west shoulder. The sun comes out and walking the rocky tundra is a pleasure; I half expect to spot a Bear, Moose, or Caribou traveling its confines, but never do. Up ahead, the roar of another hefty rapid entices me to inspect, where I find an undercut bank preceded by voluminous drops and tight maneuvering. I feel fearful of paddling these features as it has been two full years since I have done any paddling at all, and now being here alone on an extremely remote river that has likely never been packrafted before, I am reticent as I eyeball these rapids and passageways.

I’m getting tired from the bushwhacking and meandering, and when an exceptional camp spot is stumbled upon, I decide to pitch my tent and call it a day. After supper, I walk downstream slightly to inspect a potential put-in for paddling tomorrow should I accept the challenge. The little spot is ideal as it has a nice even sandy approach into the river channel with low initial consequences. I navigate back to my camp, where a night of bad dreams about dangerous rapids interrupt any chance for good rest. Early in the wee hours, a steady rain begins to fall, and feeling unrested and uneasy, I mentally cancel any possibility of paddling the beautiful Takahula River on this trip. Later, and in a steady rain, I pack up my sopping wet camp and begin the long thrash back up to the ridge above Takahula Lake, and back down to a mellow paddle to the cabin.

A few days later I’m back in Fairbanks installing gravel over the cabin site I had prepared back in June, getting myself rested, and preparing for my friend Chris Gavin’s arrival for he and I to head down to the Alaska Range for a week or two of late season packrafting before winter unveils its grinning face.

You must be logged in to post a comment.